Tsuchihashi Mining

Delivering high-quality materials from the

largest Rouseki mine in Japan.

Tsuchihashi Mining is a mine in which natural minerals such as pottery stone, Rouseki, and silica are excavated underground. Located in Bizen City, Okayama Prefecture, we are one of the very few underground mines left in the country. The excavated pottery stones are used as material by various industries such as ceramics manufacturers.

Narumi’s luxury tableware “Bone China”

Mines

Mitsuishi, the Heart of Rouseki

The Mitsuishi area of Bizen City, Okayama Prefecture where we are located, and the Yoshinaga area, which lies next to the Mitsuishi area, used to be a mining town with 40 to 50 Rouseki deposits. The following aerial map shows a current view of our mine.

Open-Pit Mining and Underground Mining

Mining methods can broadly be divided into two types. One is open-pit mining, a method in which the target mineral is excavated from the earth’s surface. The other method is underground mining, which involves digging tunnels and excavating minerals from deep inside mountains and the ground.

Most of the mines in the Mitsuishi and Yoshinaga areas carried out open-pit mining, given the advantages of this method in terms of safety and economic viability.

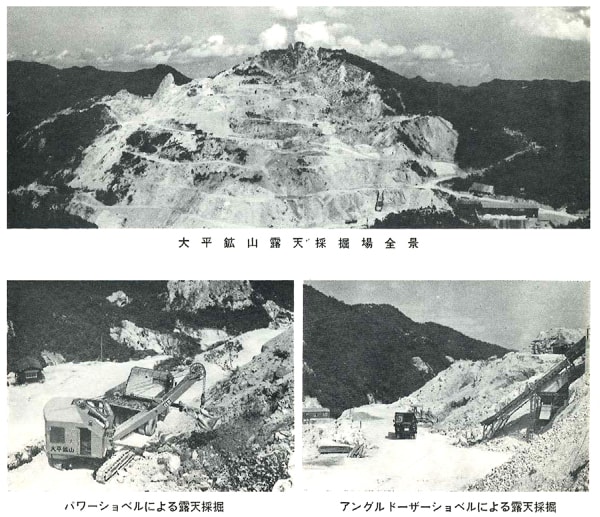

Strip mine (Ohira Mine) in those days

Source: Japan Rouseki and Mining Industry Association (Ed) / Rouseki (1964)

Our mine apparently carried out mainly open-pit mining from before the war to immediately after the end of the war. Numerous small tunnels for shoestring mining still exist on our premises. It is said that small-scale underground mining was also carried out. After the war, boring surveys were conducted, and with the discovery of excellent Rouseki deposits in the ground, all methods were completely switched to underground mining in mine development efforts.

Tsuchihashi Mining’s pithead

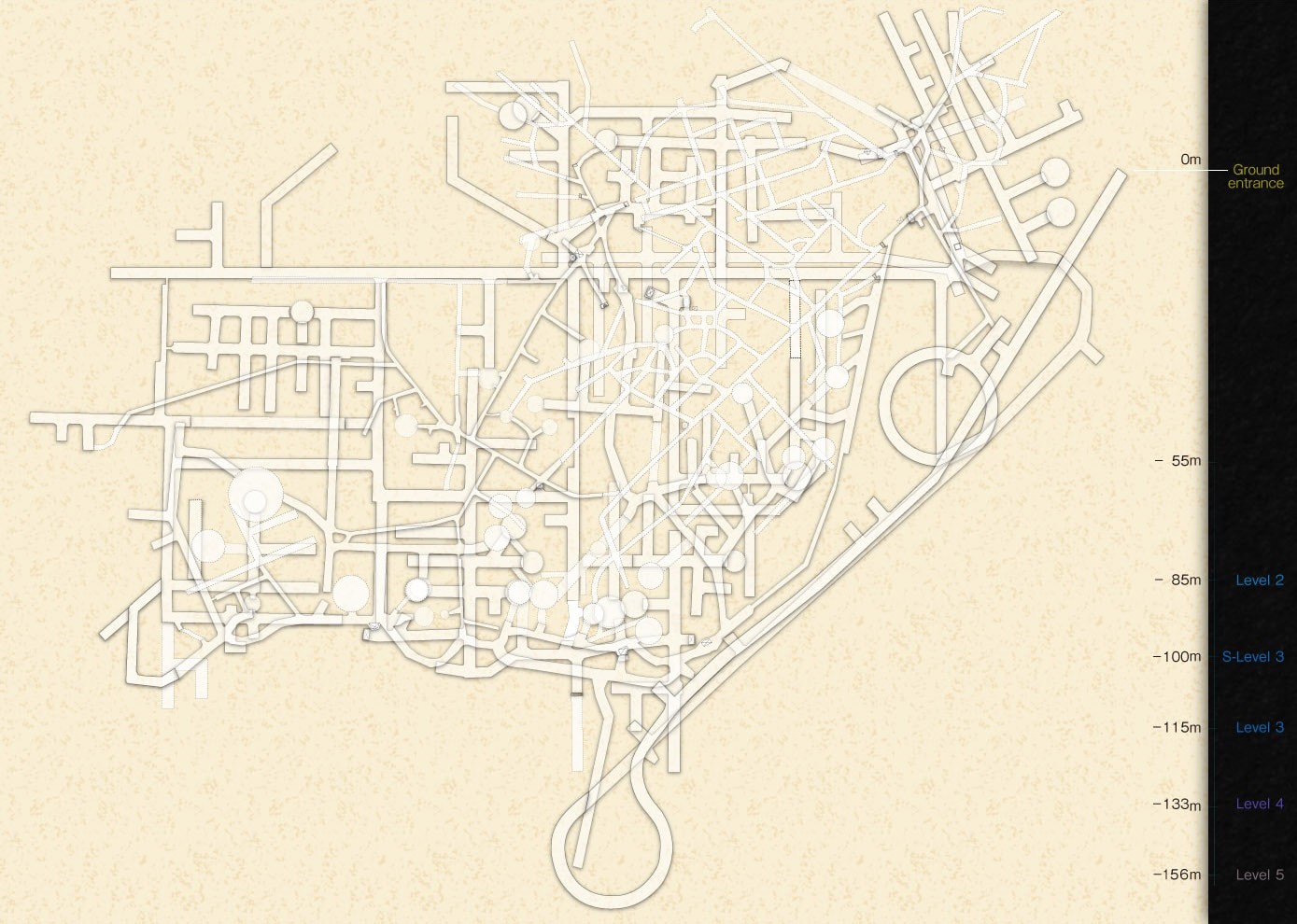

Sixty years later today, tunnels that are more than 10 km long run throughout our underground like an ant nest.

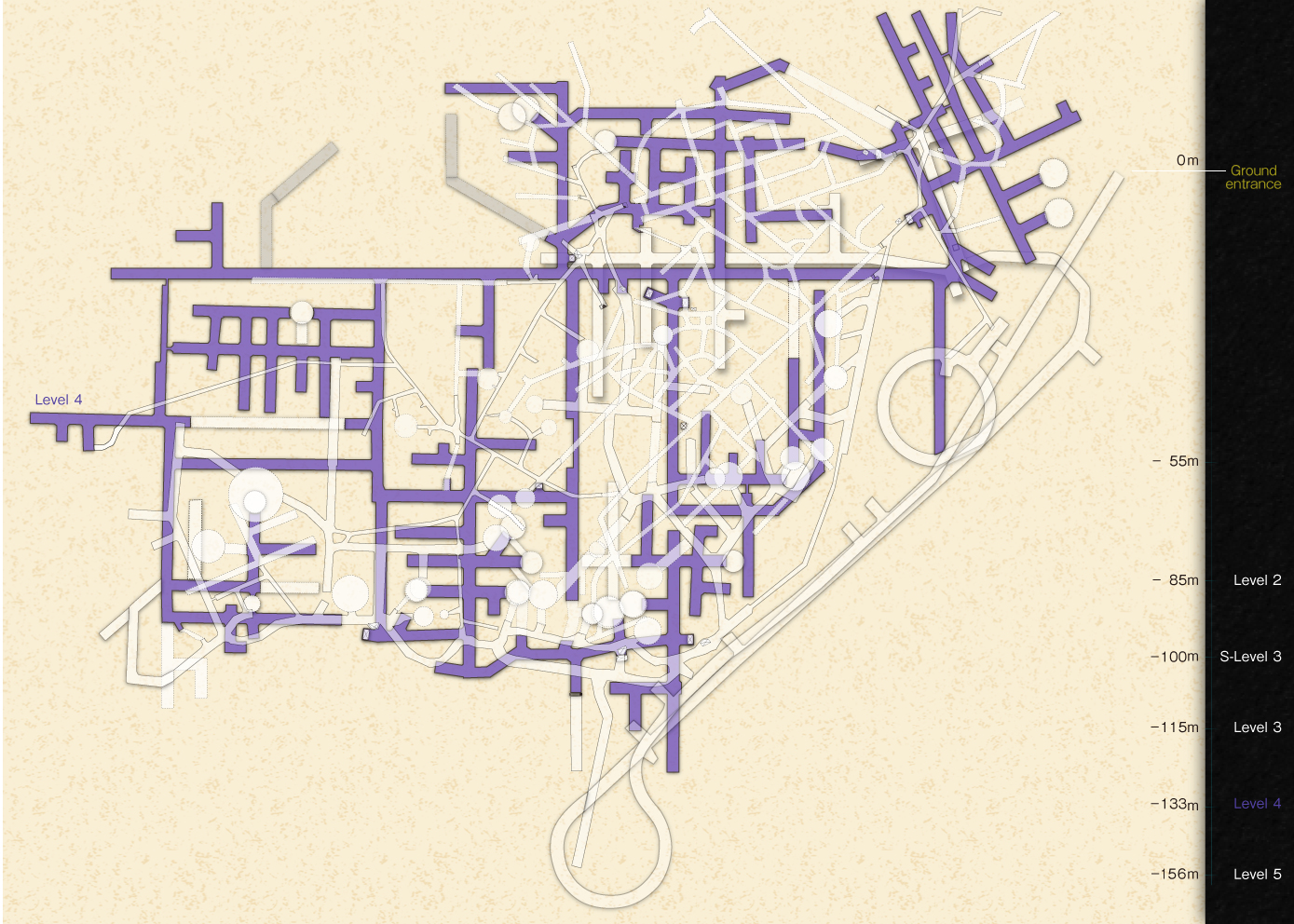

Tsuchihashi Mining/underground drawing

We presently dig down to 150 m from the ground level, and plan to dig to a depth of around 250 m in the future.

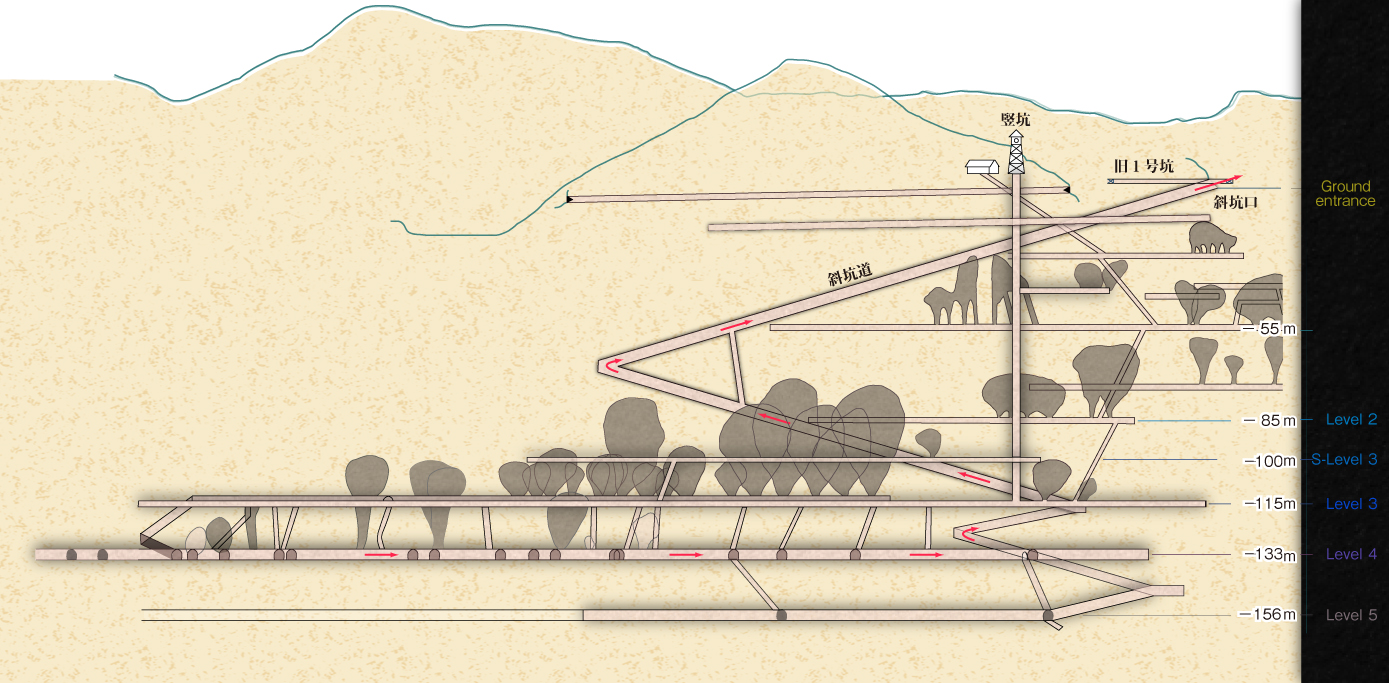

Underground/cross-section drawing

Outline of Mines and State Underground

The following shows the underground tunnel descending from the pithead above the ground.

The tunnel measures 4.5 m wide and 3.9 m high, allowing large heavy machinery and trucks to pass.

Underground tunnels made up of three layers

We have three layers of underground tunnels.

(1) L3 tunnel (−113 m)

(2) L4 tunnel (−133 m)

(3) L5 tunnel (−156 m)

(1) L3 tunnel

The L3 tunnel is situated at a level 133 m below the pithead (altitude about −130 m), comprised of old and new tunnels intertwined with each other in a complicated manner.

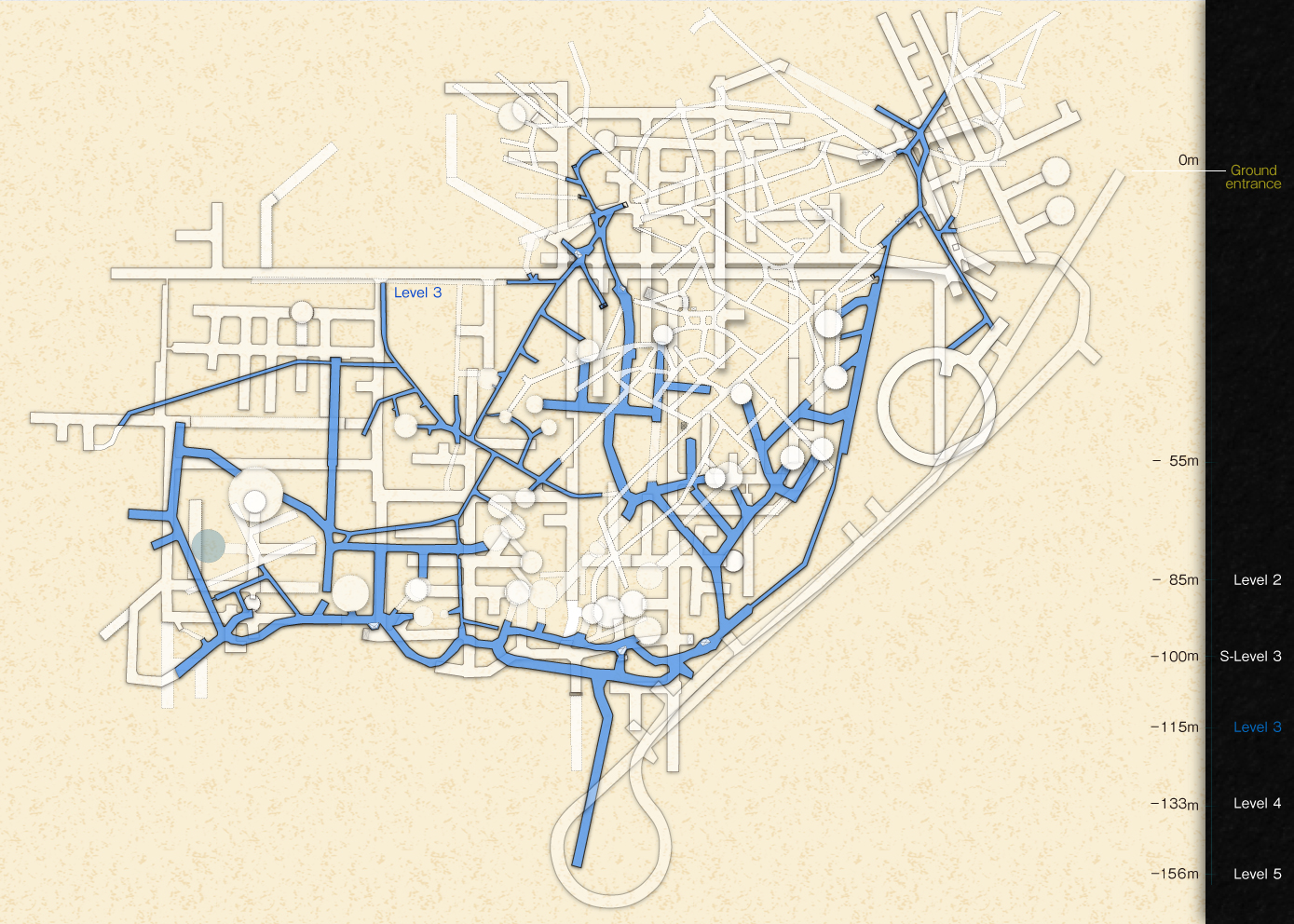

L3 Underground drawing

The old tunnels are small: 2 m wide and 2 m high. Tracks are laid out throughout the tunnels so that ore can be transported using carts. Presently, trucks are used for transportation.

State of underground track 1

State of underground track 2

Above L3 lie the L1 and L2 levels. Entry into these tunnels is prohibited as excavation has already ended and some tunnels have collapsed.

(2) L4 tunnel

The L4 tunnel is situated at a level around 133 m underground. It is equivalent to 0 meters above sea level.

L4 Underground drawing

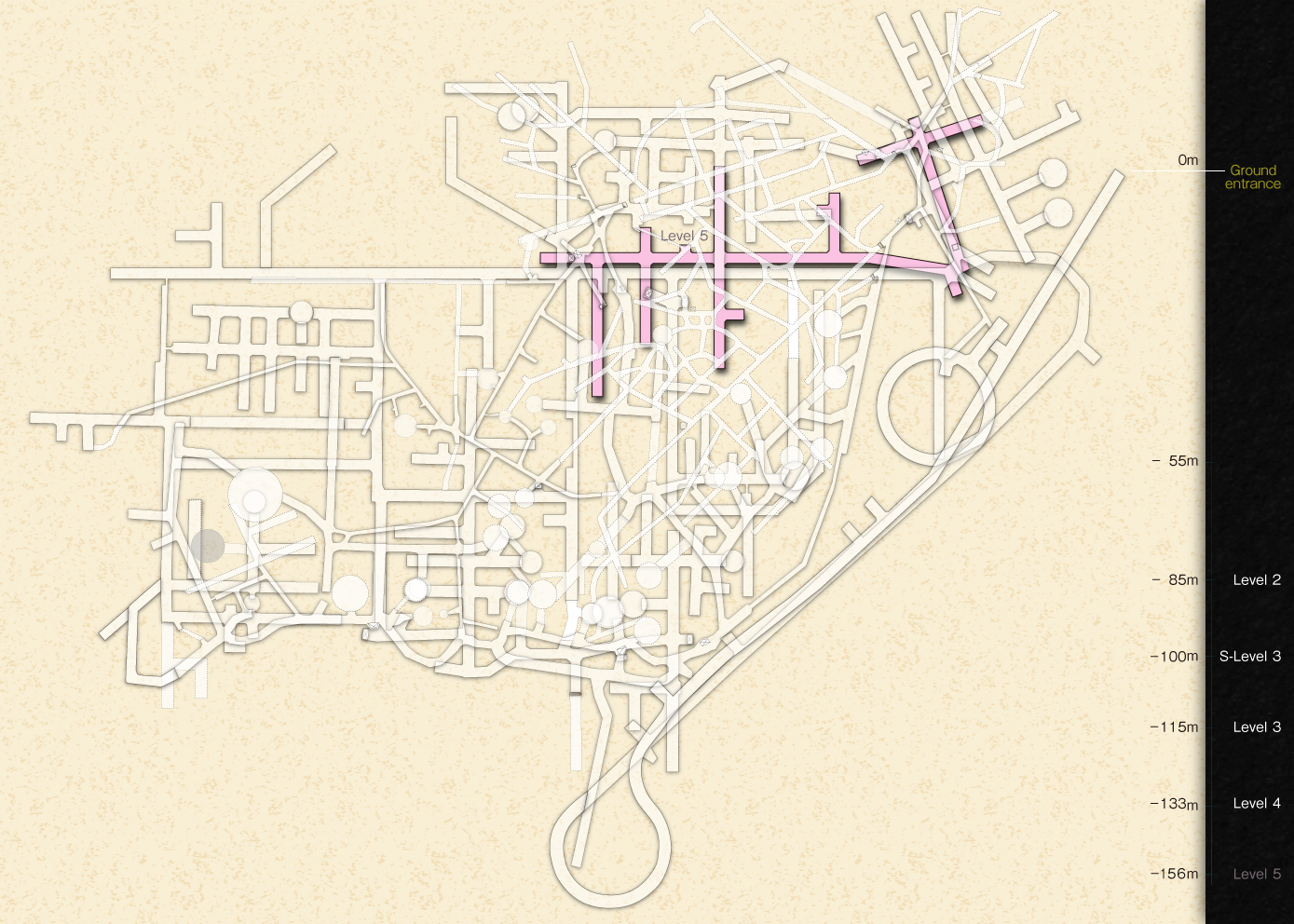

(3) L5 tunnel

The L5 tunnel is situated at a level around 156 m underground, reaching below sea level.

L5 Underground drawing

The L5 tunnel is currently being developed. Like the L4 tunnel, it will be extended widely in four directions in the future. Moving forward, L5 development will be carried out and preparations to develop the L6 tunnel below it will also be started.

The boring surveys conducted in the 50s to 60s revealed the presence of Rouseki and pottery stone deposits up to 270 m underground. Thus, we anticipate a gigantic undeveloped mine existing another 120 m below the present L5 tunnel.

History of Mitsuishi, Home of Firebricks

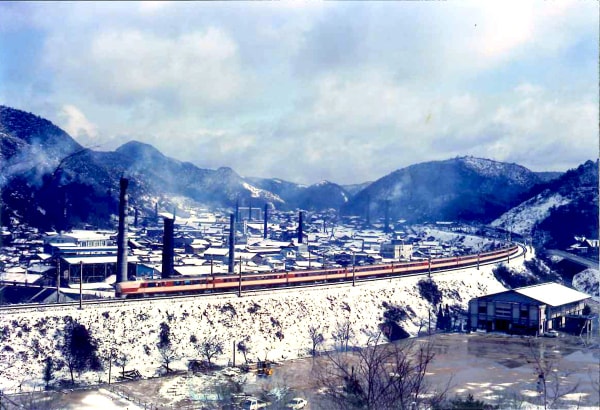

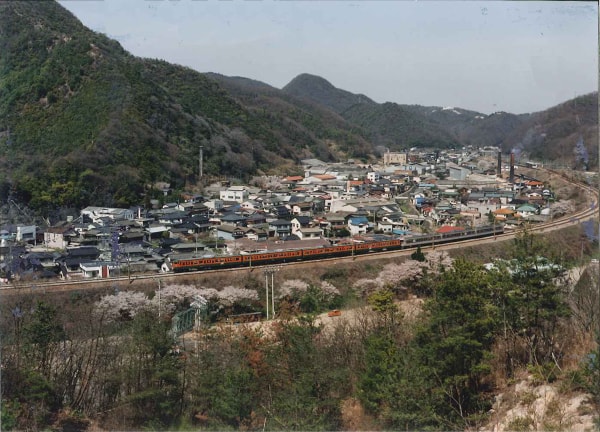

Scenery of Mitsuishi area

Mitsuishi (Bizen City, Okayama Prefecture), where our mine is located, lies at the eastern end of Okayama Prefecture. The community exists at the prefectural border adjoining Ako City, Hyogo Prefecture. The above photo shows the scenery of the Mitsuishi area as seen from the JR Sanyo Line/Mitsuishi Station. The chimney of the firebrick factory can be seen from the front. Visible in the backdrop is the gigantic Rouseki mine “Daiyama mountain” where open-pit mining used to be carried out. Presently, trees are being planted there and it has become a small hill.

Today, it is a quiet village without many people on the streets. In the past, there were countless Rouseki deposits and firebrick plants, brimming with life with many workers. The photo below shows Mitsuishi in the 60s when many firebrick improvements were carried out.

Mitsuishi in the 1960s

Photograph provided by Masataka Iga

The next photo shows the present scenery taken from more or less the same position.

Present Mitsuishi

Photograph provided by Masataka Iga

The chimneys of the firebrick factory are decreasing, replaced by residential streets.

Before the modern era, Mitsuishi used to be a checkpoint sitting on the provincial border between Harima and Bizen Provinces, and a post town on the highway route. However, with the Meiji Restoration, which brought the modernization of Japan, it became known to the outside world as the production site of “slate pencils”.

Most people who spent their childhood days during the Showa period would be reminded of the white stone resembling chalk for drawing characters and pictures on the ground when they hear the name. Those who work in the area of civil engineering and construction may still be using it for writing on concrete faces and reinforced steel.

During the Meiji Era, slate pencils played an important role at school. And with the launch of the school system, slates and slate pencils became indispensable for studying characters. There were no notebooks or pencils in those days, and people used slates and slate pencils for writing. Thus, Rouseki made in Mitsuishi served as the perfect material for the slate pencils in those days.

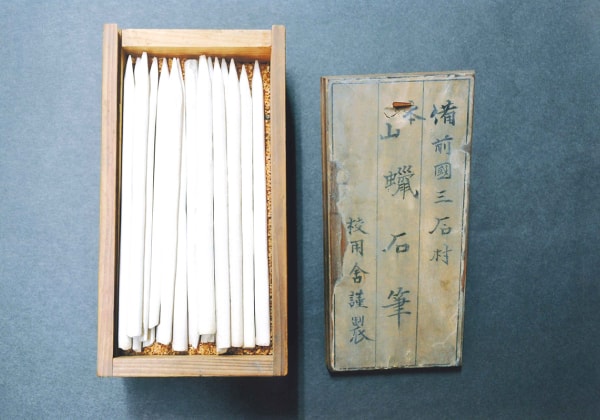

Illustration of Mitsuishi Slate Pencil in Dai Nippon

Bussan Zue

Slate pencil made in Mitsuishi

Photo provided by Koji Kinoshita

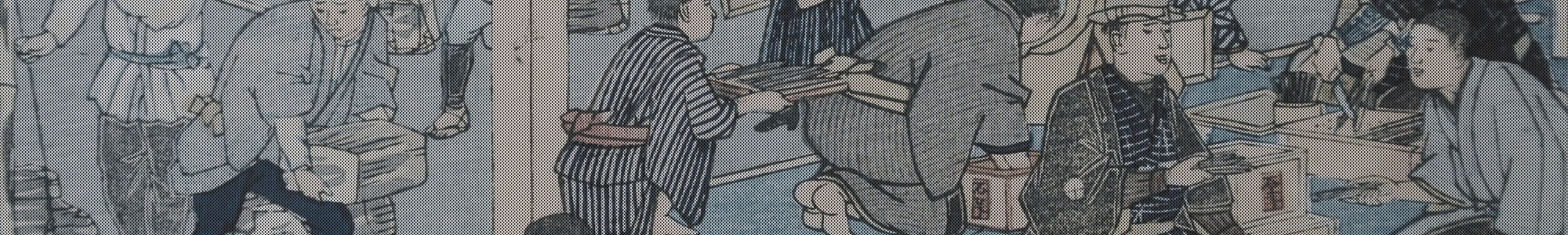

The top photo shows an actual slate pencil made during the Meiji Era. It is kept by Ohira Mine (Ohira Co., Ltd.), one of the oldest mines in Mitsuishi. Production and sales of slate pencils were carried out actively between 1872 and 1877. There are Ukiyo-e paintings (color prints) depicting such scenes at that time.

Dai Nippon Bussan Zue

Photo provided by Koji Kinoshita

Drawn by Utagawa Hiroshige III, the Dai Nippon Bussan Zue depicts famous local products of various areas in Japan. The Mitsuishi slate pencil is included as the specialty of the Bizen Province.

During the production of slate pencils, large volumes of Rouseki cutting scraps were produced. In those days, the disposal method for these scraps posed a problem.

On the other hand, the Meiji government was promoting policies to increase national prosperity and military strength, as well as develop industries, leading to the need to make iron and copper at home. Steel factories and smelters were constructed throughout Japan, and many blast furnaces were also constructed for this end. Such blast furnaces required firebricks that could withstand very high heat. In those days, the firebricks made in Japan were of poor quality and the fact that Japanese products were poorer than foreign ones was a serious problem.

Ninkuro Kato, who set up Koyosha in 1876 to manufacture and sell slate pencils in Mitsuishi, predicted that the demand for slate pencils would eventually peak, prompting him to think of a new business to start. Then one day he saw firebricks that had been made abroad, and he came up with the idea of baking bricks using the cutting scraps from the slate pencils. In this way, Ninkuro made prototypes of firebricks and went on to become a pioneering figure of firebrick-making in that area.

In 1885, Dr. Tadatsune Kochibe of the Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce, Geological Survey Center conducted a survey on Mitsuishi, and concluded that Mitsuishi’s Rouseki was rich in minerals, and made an excellent material for firebricks. In 1895, the Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce, Ad-hoc Iron-making Business Survey Committee demonstrated the excellence of firebricks made from Rouseki, and this led to the gradual increase in demand for Mitsuishi Rouseki.

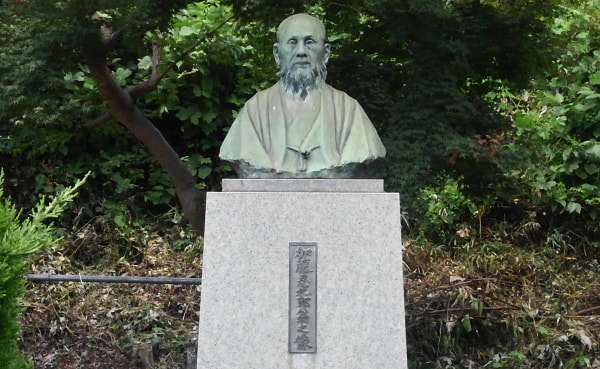

Ninkuro expanded his business using Rouseki from Mitsuishi, and focused on building the Sanyo Railway to transport Rouseki. As a result of such contributions, he became a prominent figure of the region, and is still honored by the public today. A bronze statue of Ninkuro Kato stands on the premises of the Bizen City Mitsuishi Gymnasium, and just steps away lie the tracks of the Sanyo Railway (present JR Sanyo Line).

Bronze statue of Ninkuro Kato

It is said that when Ninkuro was making prototypes of his firebricks, the baking techniques of Bizen Yaki, famous traditional ceramics of this region, came in handy. There are records indicating that the first firebricks were baked in the climbing kiln of Bizen Yaki. The fact that this region had the best material for firebricks as well as the kiln for baking bricks was a major factor helping the region to become the leading production site of firebricks.

Rouseki is also used as the material for products called clay. Unlike the meaning of clay in English, industrial clay in Japanese generally means the finely crushed powder of stones such as Rouseki and lime. The main application of clay is coating for the surface of paper. It is used to make the paper surface smooth and facilitate printing. It is also used as the filler for resin and rubber.

Like firebricks, the consumption of printed matter increased with the progress of modernization, leading to increased shipments of paper, and subsequent growth in demand for clay as a coating agent. As a result, the clay industry also grew as the main industry of the region.

Rouseki mines were searched for all over the Mitsuishi area, which is the number-one production site of both firebricks and clay in Japan, and the neighboring Yoshinaga area, and countless mines were eventually operated in both areas. The Rouseki industry enjoyed its peak just before the Pacific War; growth was sluggish for a while after the war, but it rode the waves of advanced economic growth, and enjoyed its most prosperous times in the second half of the 60s.

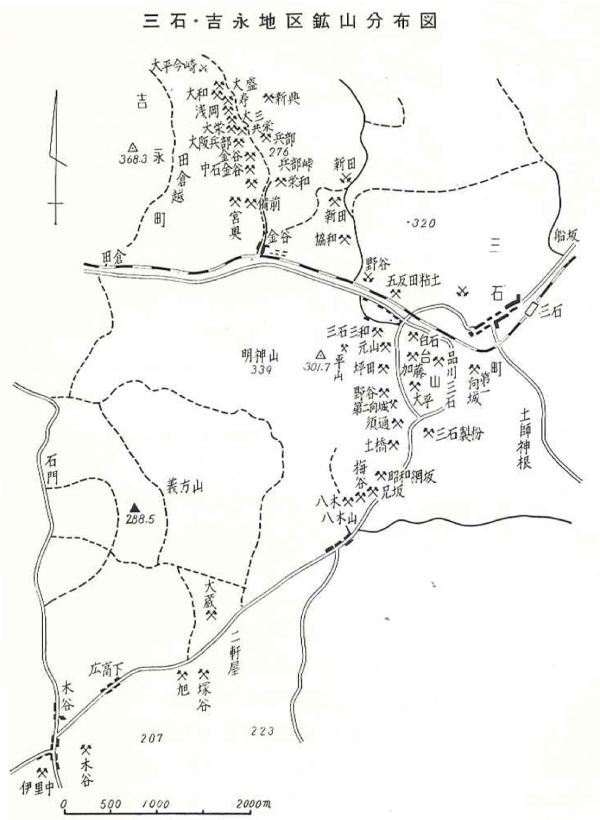

Mitsuishi and Yoshinaga mines distribution drawing

Source: Japan Rouseki and Mining Industry Association (Ed) / Rouseki (1964)

The above map shows the situation of mines in the Mitsuishi and Yoshinaga areas as of 1964.

Before the war, Mitsuishi and Yoshinaga had nearly 60 mines. Apparently, there were also many private mines excavated by individuals. However, with companies merging with each other, eventually only 35 mines were operating in 1964 (Mitsuishi area: 20 mines, Yoshinaga area: 15 mines).

Several years after the Pacific War ended, the Korean War started. Rouseki from the communist mainland China stopped coming into Japan, and it was around this time that the Mitsuishi and Yoshigawa mines made rapid leaps exceeding those before the war.

Then around 1975, most mines closed down, and today, there are only a few that are actually running. Reasons for this include bulk shipments of high-grade Rouseki coming in from Korea, and the depletion of resources at the mines.

In this flow, Tsuchihashi Mining still continues to run today because we have been supplying Rouseki mainly as the material for ceramics, which has a relatively high price compared to heat-resistant materials, and also because we have been able to excavate comparatively fine-quality ore as the material for ceramics.

Tsuchihashi Mining Mine and Geological Features

Minerals Excavated at Tsuchihashi Mining

The minerals excavated by Tsuchihashi Mining are pottery stone, Rouseki, and silica.

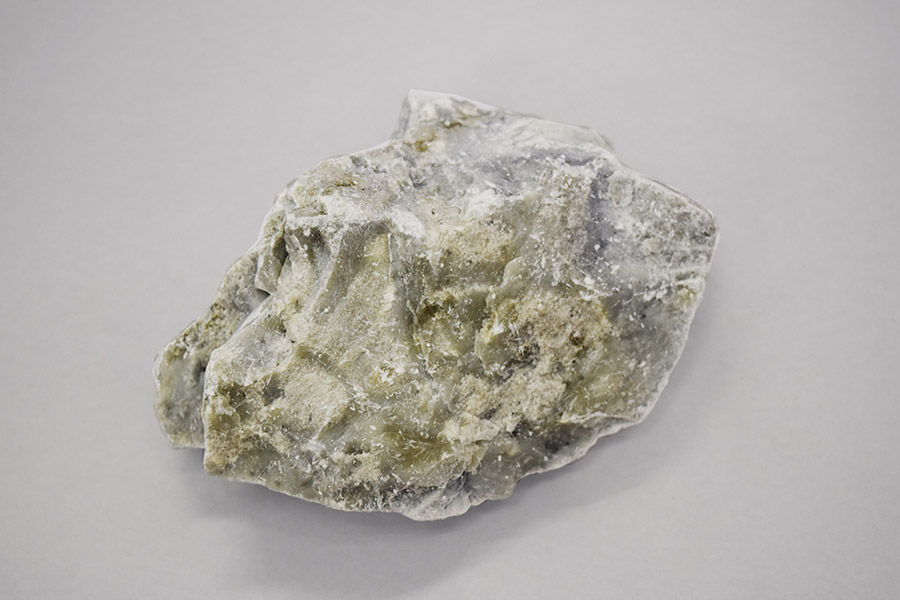

Pottery stone Special Class ore

Pottery stone (sericite)

Very brittle. Basically grayish white in color, but some faces may appear green, pink, black, etc.

All become white when crushed.

Rouseki (pyrophyllite)

Rouseki (pyrophyllite)

Unique waxy texture. Very brittle. Cracks along the joints of the rock.

Slightly grayish white in color, but appears blue when seen from a distance.

Silica ore

Silica

Hard but easy to crush using a hammer, etc. Comes in white, purple, black, etc.

Takes various colors according to the worked surface. Porous.

Rouseki is the general name for minerals with a waxy texture such as pyrophyllite, kaolinite, sericite, etc. Of these, sericite Rouseki is traditionally called pottery stone to differentiate it from the others. On the other hand, silica used to be considered waste rubble in Mitsuishi, and companies involved in landfilling and cement were asked to take it away. But given its white color, excellent crushability, and fine quality, silica is now an important product.

Mitsuishi’s mine was created during the Cretaceous

Period

When did Mitsuishi’s Rouseki mine form?

Generally, the Rouseki mine is thought to have been created by the reaction between acidic hydrothermal solution and host rock (tuff repository). The Rouseki mines in the Mitsuishi area are said to have been formed during the Cretaceous Period (145 million to 65 million years ago).

The Cretaceous Period is the last era in which dinosaurs ruled the earth, and at the end of the period, these dinosaurs became extinct. During this period, which lasted for 70 million years, volcanic activity increased in the latter half of the period, resulting in the present mines. All the Rouseki deposits in the Chugoku Region are said to have been formed during the latter half of the Cretaceous Period. Other than Mitsuishi, the same applies for the Abu and Susa mines in Yamaguchi Prefecture, and the Shokozan mine in Hiroshima Prefecture.

Based on the dating technique using potassium (K) contained in our sericite, survey results date our mine back about 80 million to 73 million years ago.

(Reference: Hidetomo Hongu, Takashi Kitagawa, Hiroshi Nishido: Modes of Occurrence and K-Ar Ages of “Rouseki” Deposits in Mitsuishi Area, Okayama Prefecture Clay Science 40(1): 46–53)

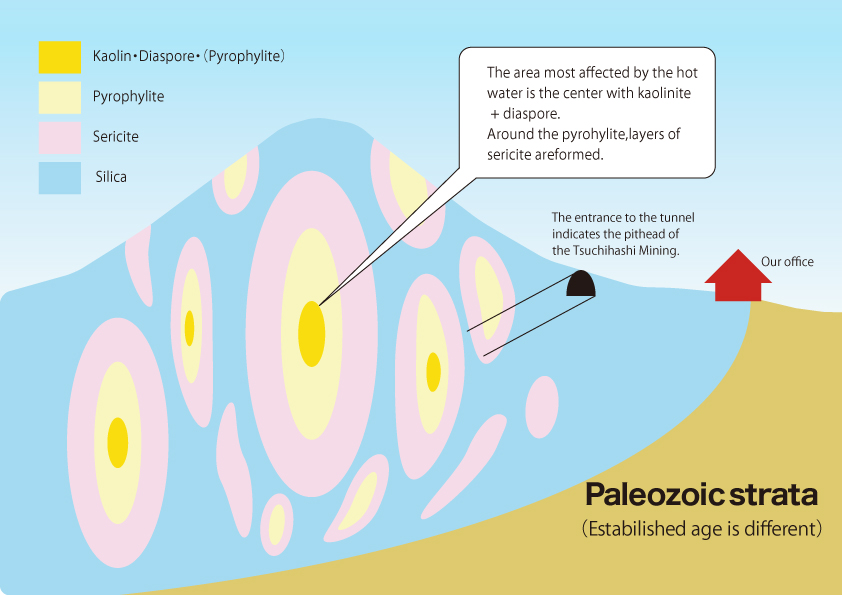

Illustration of mine (Assumed)

Here, Tsuchihashi Mining’s Rouseki mine is described using a simplified illustration.

Illustration of mine

This is a simplified illustration. The actual mine has a more complicated shape. Here, it has been simplified for clarity. The red building inside is our office, and the entrance to the tunnel indicates the pithead of the Tsuchihashi Mining.

During the Cretaceous Period 70 million years ago, hot water is thought to have started to boil under the Mitsuishi area where our mine is located, and be discharged towards the ground via the bedrock. At the time, the areas most affected by the hot water were pyrophyllite + kaolinite, or pyrophyllite + kaolinite + diaspore. In any of these cases, these areas contained very little sodium (Na), potassium (K), magnesium (Mg), and calcium (Ca). Silica and alumina are the main components.

Around the pyrophyllite + kaolinite area that was severely affected by the hot water is the sericite mine, which was only slightly affected by the hot water. Sericite contains K (potassium). When the thick layer of sericite is exceeded, the silica layer spreads to the outside. Silica contains 98–99% SiO2. It is comparatively pure and contains trace amounts of alumina and other minerals.

The area most affected by the hot water is the center with kaolinite. Even in our mining area, some places produce very pure kaolinite, but there are not many of these places. It is rare for kaolinite to be produced on its own; usually, it is accompanied by pyrophyllite and diaspore. Moreover, diaspore is produced even less frequently. While production of kaolinite is small, instead the pyrophyllite layer spreads out extensively.

Around the pyrophyllite, layers of sericite are formed. In Rouseki deposits, this sericite layer makes up the widest area and it is also a thick layer. Enveloping these Rouseki deposits is an extensive layer of massive amounts of silica. In our mining areas, silica is produced throughout the region.

The incidental state of deposits shown in the illustration is called a “lens shape”. Deposits formed in this lens shape have various sizes and grades depending on the effects of the hot water. Distribution in the ground is also very irregular. We regularly conduct boring surveys underground to determine the details of the incidental state of irregular deposits, and then devise mining plans and develop tunnels accordingly.